“Insurance works on seven key principles — utmost good faith, insurable interest, indemnity, contribution, subrogation, proximate cause, and loss minimization. These principles ensure fairness, prevent fraud, and protect both insurers and policyholders.”

Byline: Written by a practicing insurance professional with 15+ years’ experience in underwriting and claims. Practical insights in this guide draw on industry practice and authoritative sources (see IRMI, OECD, Insurance Information Institute).

In today’s fast-changing world, understanding the principles of insurance is not just academic — it’s practical. These principles explain how insurance contracts work, why insurers require honest answers, and how claims are settled so policyholders receive financial protection when loss occurs.Think of it this way: if a car owner bought a policy after an accident, without rules like insurable interest and utmost good faith, insurers would be unable to price risk or pay claims fairly. These principles keep the system solvent and trusted.

Table of Contents

ToggleKey Notes;

- 7 core principles of insurance form the foundation of every insurance contract.

- They ensure fairness, transparency, and reliable financial protection for policyholders and insurers.

- The principle of indemnity ensures you’re compensated for actual loss, not profit.

- Subrogation and contribution prevent double payouts and share recovery fairly among insurers.

- Without these principles (and good faith), many insurance plans and life or property coverages would be unenforceable.

Want deeper practical guides? See our pages on life insurance, health insurance claims, auto insurance & subrogation, and business insurance.

Understanding Insurance: An Overview

Insurance is a fundamental tool to protect your finances from unexpected events. At its core, an insurance policy is a legally binding agreement between an insurer and a policyholder that transfers specific risks in exchange for a premium. Properly designed insurance policies spread losses across many insureds so individuals and businesses can manage financial exposure to risk.

Knowing the basics of insurance improves decision-making and builds trust between parties: insurers need accurate information to underwrite risk, and insureds need clear contract terms to know what protection they have. This mutual transparency is the practical foundation of the principles of insurance and of any sound insurance contract.

Note for readers in India: regulatory bodies such as IRDAI govern local licensing, product filings, and consumer protections; for international readers, similar rules exist through national regulators and supranational guidance (see IRMI, Insurance Information Institute, OECD for comparative perspectives).

| Principle | Description (short) | Quick example |

| Utmost Good Faith | Both parties must disclose material facts honestly. | Not disclosing a relevant health condition can lead to claim denial. |

| Proximate Cause | The dominant, effective cause that leads to loss determines coverage. | Fire caused by earthquake — if earthquake is excluded, coverage may be denied. |

| Insurable Interest | Policyholder must stand to suffer financially from the insured loss. | Mortgagee has interest in the mortgaged property. |

| Indemnity | Compensation restores the insured to their pre-loss financial position. | Car repair paid up to current market value, not original invoice price. |

| Subrogation | Insurer can recover from a third party responsible for the loss. | Insurer sues at-fault driver’s insurer after paying your collision claim. |

| Contribution | When multiple policies cover the same interest, insurers share the loss. | Two property policies prorate payment based on their sums insured. |

| Loss Minimization | Insured must take reasonable steps to prevent or reduce loss. | Calling emergency services and shutting off utilities after a leak. |

Quick fact: the global insurance market is large and varied — for context see Swiss Re/III/OCED reports for recent premium and market-size figures. Use the table above as your road map — each principle below is explained with practical examples and regulatory notes.

What Are the Principles of Insurance?

Knowing the principles of insurance is essential for both insurers and insureds. These rules create a predictable framework for underwriting, pricing, and claims so contracts are fair, enforceable, and focused on genuine financial protection. In practice, they reduce fraud, support solvency, and make risk sharing possible.

Defining the Foundation of Insurance Contracts

Below are the seven core insurance principles that underpin most insurance contracts worldwide. Each principle will be explained in detail later with a practical example and a reference to authoritative guidance (IRMI, Insurance Information Institute, OECD).

- Utmost Good Faith (Uberrimae Fidei) — Parties must disclose material facts honestly (example: failing to disclose a smoking habit on a life application can lead to claim denial).

- Insurable Interest — The policyholder must stand to suffer a financial loss from the insured event (example: a mortgagee’s interest in a mortgaged home).

- Indemnity — Compensation aims to restore the insured to their pre-loss financial position, not create profit (example: a homeowner reimbursed for repair costs up to actual loss).

- Subrogation — After paying a claim, the insurer can pursue the third party that caused the loss to recover amounts paid (example: insurer sues the at-fault driver’s insurer after settling your collision claim).

- Contribution — If multiple policies cover the same loss, insurers share the payment so the insured does not recover more than the actual loss (example: two property policies prorating a $50,000 loss).

- Loss Minimization (Duty to Mitigate) — The insured must take reasonable steps to prevent or reduce loss (example: shutting off water and calling emergency services after a burst pipe).

- Proximate Cause — Liability turns on the dominant or effective cause of loss, not necessarily the last link in a causal chain (example: if an excluded peril triggers a covered peril, proximate-cause analysis determines coverage).

The Importance of Principles in Risk Management

These principles insurance professionals apply daily to keep the system working. They improve risk management at every level — from individual insured property coverage decisions to enterprise risk programs. According to industry reports (Swiss Re / Insurance Information Institute), the global insurance market involves trillions in premiums annually; applying these principles helps maintain market stability and consumer trust. Each subsequent section of this guide goes deeper into one principle with examples, a short legal/regulatory note, and practical tips for policyholders and agents.

Principle of Utmost Good Faith

The principle of utmost good faith (uberrimae fidei) requires both parties to an insurance contract to disclose all material facts honestly and completely. In underwriting and claims, insurers rely on truthful answers about risk — health, occupation, past claims, and other material circumstances — to price and accept risk fairly.

Understanding Uberrimae Fidei in Insurance

As an underwriter with 15+ years’ experience, I routinely see claim problems caused by incomplete disclosure. Commonly required disclosures include medical history, hazardous occupations or hobbies, previous claims, and any material facts the insurer asks for on the proposal form. This duty is broader than ordinary good faith in commercial contracts and is a distinctive feature of insurance law (see Marine Insurance Act 1906 for historical origin; check IRDAI/local regulator guidance for jurisdictional specifics).When you complete an application, you sign a statement that information is true to the best of your knowledge. Practically speaking, insured must answer honestly and proactively ask clarifying questions if a proposal question is unclear.

Consequences of Non-Disclosure in Contracts

Failure to disclose material facts can lead to repudiation of a claim, policy avoidance, or policy cancellation. Typical consequences include:

| Aspect | Description |

| Obligations | Both parties must act honestly and disclose all relevant information; the insured’s duty is particularly strict. |

| Legal Framework | Principle rooted in the Marine Insurance Act 1906 and applied under many common-law systems; local regulators (e.g., IRDAI, NAIC) and courts shape application in each jurisdiction. |

| Risks of Non-Disclosure | Claims may be denied; policies can be voided from inception; insurers may recover paid amounts where fraud is found. |

| Responsibility | Insured individuals carry a heavier burden for accuracy; agents and brokers must also disclose material facts and clarify questions. |

Practical tip: keep a written record of disclosures and obtain copies of proposal forms. If unsure whether a fact is material, disclose it — nondisclosure is a common and avoidable reason for claim disputes. For further reading, see IRMI and Insurance Information Institute explainers and your local regulator’s guidance.

Principle of Insurable Interest

The principle of insurable interest prevents insurance from becoming a speculative bet: the person taking the policy must have a genuine financial stake in the insured subject or life. This requirement protects insurers and policyholders by reducing moral hazard and fraud and by ensuring an insurance contract reflects a real economic interest.

Significance of Financial Interest in Insurance

In practice, insurable interest is essential for both life insurance and general insurance lines. Without it, courts and regulators can deem a policy void. As an underwriting professional with 15+ years’ experience, I’ve seen lenders, employers, and owners use insurable interest to secure financing and manage business continuity — but they must document the interest clearly.

Common forms of insurable interest include:

- Contractual interest — arising from contracts (e.g., a leaseholder insuring leasehold improvements).

- Proprietary/ownership interest — the owner of an asset (e.g., homeowner insuring property).

- Statutory interest — created by law (e.g., certain creditor interests).

Examples of Insurable Interest in Practice

Practical scenarios help clarify who has an insurable interest:

| Relationship | Type of Insurable Interest |

| Property owner | Full insurable interest in owned assets (e.g., house, business premises). |

| Spouses | Mutual insurable interest in each other’s life (varies by jurisdiction). |

| Parents | Insurable interest in minor children’s lives (financial dependency). |

| Employers | Insurable interest in key employees (e.g., key-person life cover) or employees where agreed by contract. |

| Creditors | May have insurable interest in debtor’s life or property where there’s a secured loan; consent/assignment may be required. |

| Tenants | Insurable interest in fixtures, contents, or leasehold improvements depending on lease terms. |

How to Prove Insurable Interest (Checklist)

- Ownership documents (title, mortgage statements) for property.

- Loan or security agreements showing creditor interest.

- Marriage or birth certificates for family-based interests.

- Employment contracts or business records for employer-employee interests.

Example (real-world): A bank with a mortgage on a house can require the borrower to maintain property insurance naming the bank as mortgagee. If the house is destroyed, the mortgagee’s interest is protected — payout first satisfies outstanding loan. Courts have voided policies where no insurable interest existed at inception, so confirmation at policy issue matters.

References & practice notes: authoritative explanations of insurable interest are available from IRMI and Investopedia for definitions, and local regulators (e.g., IRDAI for India, state regulators in the U.S.) set jurisdictional rules. When in doubt, document and disclose the relationship that creates the interest — it keeps claims straightforward and enforceable.

Principle of Indemnity

The principle of indemnity ensures that an insured party is restored to their pre‑loss financial position after a covered event — not placed in a better position. In other words, insurance compensates for actual loss, preventing unjust enrichment and limiting moral hazard.

For example, if business stock with a market value of ₹200,000 (approx. USD 2,400 at the time of writing) is destroyed, indemnity means the claimant is compensated for that ₹200,000 loss — even if the insured had originally declared a higher sum. Using a neutral currency or local figures is fine, but always include authoritative valuation evidence when filing a claim.

In motor claims, indemnity typically means repair costs or market‑value settlement after depreciation is applied. In health insurance, indemnity cover pays actual medical bills up to policy limits (subject to co‑payments and exclusions) — the insured does not “profit” from the event. This is why claims documentation (invoices, bills, medical records) is essential: insurers base payment on demonstrable actual loss.

Note the key exception: life insurance is not generally governed by indemnity. Life policies provide a pre‑agreed sum on death or upon a specified event, because the loss (the death of a person) cannot be quantified as an actual monetary loss in the same way as property damage. This is why life cover and general indemnity products follow different legal and underwriting rules.In some property and specialty lines, parties agree an agreed value before loss — an Agreed Value Policy — which fixes the sum payable on total loss and overrides traditional indemnity calculations (useful for classic cars, fine art, or specialized equipment).

The table below shows how the principle of indemnity works in different insurance types:

| Insurance Type | Application of Indemnity | Compensation Method |

|---|---|---|

| Property Insurance | Yes | Based on actual loss incurred |

| Life Insurance | No | Fixed benefit regardless of loss |

| General Insurance | Yes | Depreciated value of assets |

| Agreed Value Policies | Applicable | Pre-determined value agreed by both parties |

The principle of indemnity helps avoid fraud in insurance. It aims to put the insured back to their financial state before the loss. This keeps the insurance industry ethical.

Worked example (illustrative)

Suppose a car’s market value before a crash is $8,000. The insurer pays repairs of $5,000. Depreciation on a replaced part reduces settlement value by $500. The insured’s net indemnity payment is adjusted by policy excess/deductible; the insured cannot claim more than the actual economic loss.

Practical tip (EEAT): as a claims officer for many years I recommend documenting pre‑loss condition (photos, service history) and keeping all invoices — this speeds settlement and avoids disputes about actual loss. For authoritative discussion of indemnity and examples, consult IRMI, Insurance Information Institute, and your local regulator (e.g., IRDAI or state insurance department).

Principle of Subrogation

The principle of subrogation gives an insurer the right to step into the shoes of the insured after paying a claim and recover amounts from a responsible third party. Subrogation prevents the insured from being double‑compensated, keeps premiums lower over time, and ensures the ultimate wrongdoer bears the cost.

How Subrogation Protects Insurers

Subrogation matters because it allows insurers to recoup paid claims and control loss costs. Typical subrogation scenarios arise in motor and liability claims: the insurer pays your loss and then pursues the at‑fault party (or their insurer) for recovery. Practical documents for a subrogation action include the police report, photographs, repair invoices, witness statements, and the insurer’s claim file.

There are generally three ways subrogation arises: contractual (expressly reserved in the insurance policies), legal (arising from statutory or common‑law rights), and equitable (where fairness allows recovery even without a strict legal basis). The precise categories and remedies vary by jurisdiction, so consult IRMI or local regulator guidance for details.

Real-world example: after a rear‑end collision caused by Driver B, Insurer A pays Insured’s repair costs. Insurer A then pursues Driver B’s insurer to recover the amount paid. The insured must normally cooperate (provide statements, assign rights) — failure to cooperate can jeopardize recovery and may affect the insured’s claim.

Understanding Third-Party Claims

Third party claims are central to subrogation: the insurer enforces the insured’s right against the responsible third party to recoup payments. Note a common commercial pitfall: signing a contractual waiver of subrogation (for example, in leases or construction contracts) can prevent the insurer from recovering and may increase your insurance costs — avoid waivers unless necessary and understand the premium implications.

Practical tip: preserve evidence at the scene, notify your insurer promptly, and share any third‑party correspondence. For further reference on process and case law, see IRMI and NAIC/III resources and jurisdictional guidance from regulators (e.g., IRDAI in India).

| Type of Subrogation | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Contractual | Included in insurance policies when the insured causes damage to a third party. | Insured party damages another vehicle. |

| Legal | Arises when the insured is injured due to a third party’s fault. | Insured claims compensation from the negligent party’s insurer. |

| Equitable | Allows recovery without contractual origin. | Insurer recovers loss from a party voluntarily during negotiations. |

Principle of Contribution

The principle of contribution ensures fairness when an insured has multiple insurance policies covering the same interest and risk. Rather than allowing the insured to recover more than the actual loss, contribution requires insurers to share the payout so the insured is indemnified but not enriched.

Preventing Profiteering from Insurance Claims

Contribution applies only when: (1) at least two policies are in force, (2) the policies cover the same subject-matter and the same interest, and (3) the loss is of a kind insured by each policy. Note: contribution generally does not apply to most life insurance and personal accident policies (these are typically non-contributory).

Common method — proportional contribution: each insurer pays a share of the loss in proportion to its sum insured relative to the total sums insured across all policies. The formula is:

Insurer’s share = (Insurer’s sum insured / Total sum insured across policies) × Loss amount.

Worked example

Suppose a property suffers a $50,000 loss and there are two policies: Policy A sum insured $30,000; Policy B sum insured $50,000. Total sum insured = $80,000.

- Policy A share = (30,000 / 80,000) × 50,000 = $18,750

- Policy B share = (50,000 / 80,000) × 50,000 = $31,250

This ensures the insured receives $50,000 (the actual loss) but neither insurer pays more than its fair proportion.

Practical notes for policyholders and practitioners

- Report all relevant policies when making a claim — late disclosure of additional coverages can delay settlement.

- Insurers verify overlap via policy numbers, insured interests, and effective dates; keep copies of your insurance policy documents accessible.

- Some policies (e.g., primary vs. excess layers) have clear priority clauses — read the policy terms to understand how contribution will operate.

- If a dispute arises, regulatory guidance and case law (see IRMI/III references) clarify application in different jurisdictions.

As a claims professional, I advise documenting all policies at the outset and giving insurers permission to liaise — cooperation accelerates the contribution calculation and settlement. For further reading and jurisdictional rules, consult IRMI and your local regulator (for example IRDAI in India or the state insurance department in the U.S.).

Principle of Loss Minimization

The principle of loss minimization (also called the duty to mitigate) requires the insured to take reasonable steps to prevent or reduce loss once an insured peril is imminent or has occurred. This duty applies to individuals and businesses alike: immediate actions can preserve value, speed recovery, and influence the outcome of an insurance claim.

Duty of the Insured to Mitigate Loss

From my 15+ years handling claims, I can say that prompt, reasonable action often makes the difference between a smooth settlement and a disputed claim. As soon as loss or damage is discovered, the insured must take reasonable steps — for example, shut off utilities after a burst pipe, call emergency services for a fire, or secure property after a break-in. Failure to take reasonable steps can reduce the indemnity or, in extreme cases, lead to repudiation if the insurer can show prejudice.

Strategies for Effective Loss Prevention

Implementing simple, practical measures before and after a loss reduces frequency and severity of claims. Below are proven strategies that both policyholders and risk managers should follow:

- Regular Maintenance: Routine inspections and repairs (roof, wiring, HVAC) prevent deterioration and reduce the chance of covered losses.

- Timely Incident Reporting: Notify the insurer promptly — early reporting helps preserve evidence and accelerates claim handling.

- Safety Training: Employee or household safety training reduces accidents and liability exposure.

- Security Measures: Alarms, locks, cameras and secure storage deter theft and vandalism and can be required by underwriters.

Emergency Plans: Written procedures (evacuation, shutdown, data backup) minimize panic and cascading damage.

| Strategy | Description | Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Regular Maintenance | Routine checks and repairs on property | Prevents larger issues and costly repairs |

| Timely Incident Reporting | Notify insurer promptly after an incident | Initiates claims process quickly |

| Safety Training | Educating about safety protocols | Reduces the likelihood of accidents |

| Security Measures | Use of alarms and surveillance systems | Deters criminal activity and loss |

| Emergency Plans | Preparedness for crises | Minimizes panic and potential losses |

Practical checklist for immediate actions after a loss: (1) ensure safety, (2) call emergency services if needed, (3) contact your insurer, (4) preserve evidence (photos, damaged items), (5) keep receipts for emergency repairs. These are the reasonable steps insurers expect you to take.

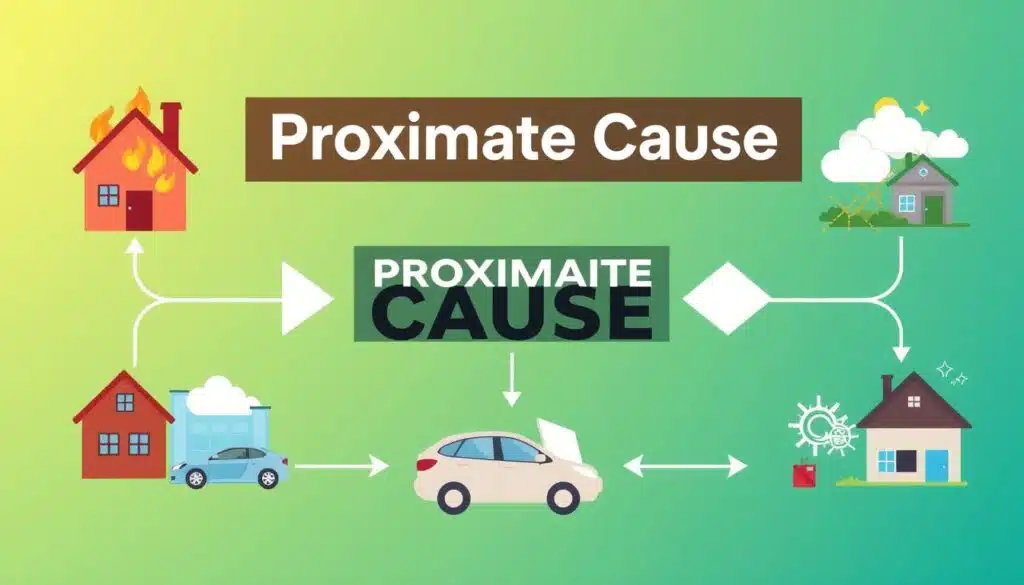

Principle of Proximate Cause

The principle of proximate cause determines which peril is the dominant, effective cause of loss for the purposes of coverage. Policies cover named perils and sometimes excluded perils; proximate-cause analysis identifies whether the covered peril or an excluded peril was the efficient cause that set the chain of events in motion.

Proximate cause is not always the last event before loss; it is the closest or most significant cause in the causal chain. For example: a small kitchen fire (covered) triggers sprinkler activation that causes water damage; proximate-cause analysis may find the fire — a covered peril — is the dominant cause, so water damage is covered. Conversely, if an excluded peril (e.g., earthquake) directly causes subsequent covered damage, coverage may be denied if the excluded peril is the proximate cause.

Legal frameworks and case law (see IRMI, and in the UK the Insurance Act 2015) influence proximate-cause interpretation in each jurisdiction. Practically, insurers and courts look at the facts, timing, and sequence of events to decide which peril is dominant.

Example scenario: Faulty wiring causes a fire that damages inventory, and then heavy rain (unrelated and excluded) causes secondary flooding. If the fire was the efficient cause and fire is covered, the claim for inventory may be payable; if the excluded peril was the proximate cause, coverage could be denied.

| Factor | Description |

|---|---|

| Definition | The cause closest to the loss event, determining the insurer’s liability. |

| Importance | Essential for establishing eligibility for insurance claims. |

| Application | Relevance in situations involving multiple risks, some insured, some excluded. |

| Legal Framework | Influenced by laws such as the UK Insurance Act 2015. |

| Responsibility | Lowers the liability of defendants by pinpointing the immediate cause of damage. |

Teaching scenario: imagine a vehicle struck a fallen tree in a storm; rain then floods the engine. Determine the proximate cause by asking which event set the chain of loss in motion and which was the dominant factor; that analysis decides coverage.

Practical tip: document causes, timelines, and evidence at the scene (photos, timestamps, witness statements). When in doubt, insurers and policyholders should rely on expert reports (fire investigators, engineers) to establish proximate cause. For authoritative guidance, consult IRMI, Insurance Information Institute, and your local regulator’s technical notes.

Common Types of Insurance Coverage

Understanding the main types of insurance helps you choose the right insurance policy for protection and long‑term financial security. Broadly, coverages split into life insurance (products that pay a benefit on death or maturity) and general insurance (property, liability, health, vehicle—covering losses that can be quantified).

Life Insurance vs. General Insurance

Life insurance provides financial protection to dependents or beneficiaries when the insured dies (or on certain life events). Common life products include:

- Term insurance — pure life cover for a specified period (cost‑effective life cover for many households).

- Endowment plans — combine savings with life cover; pay a benefit on maturity or death.

- Money‑back plans — periodic payouts during the policy term plus sum assured on death.

- Savings plans — long‑term accumulation for goals (retirement, education).

- Child education plans — structured savings with life protection for parents.

- Unit Linked Insurance Plans (ULIPs) — combine investment with life cover (investment risk with potential upside).

General insurance protects against specific, quantifiable losses and is typically indemnity‑based. Key categories include:

- Health insurance (medical/Mediclaim) — covers hospitalisation and medical costs.

- Vehicle insurance — covers damage to vehicles and third‑party liability.

- Home/property insurance — covers physical damage to buildings and contents.

- Fire & hazards insurance — protects businesses and property from fire and allied perils.

- Liability insurance — covers legal liability to third parties (e.g., public liability, professional indemnity).

Essential Types of Coverage to Consider

Choose coverages that match your risk exposure, financial goals, and regulatory requirements. Below are widely recommended lines to consider for comprehensive protection:

| Type of InsuranceDescription | |

| Health Insurance | Covers medical treatment costs, hospitalization, and sometimes critical illness benefits — reduces medical financial burden. |

| Car Insurance | Mandatory in many jurisdictions; covers damage to your vehicle and third‑party injury or property damage. |

| Homeowners / Property Insurance | Protects homes and business premises from fire, theft, storm, and other perils. |

| Travel Insurance | Covers trip cancellation, lost baggage, and emergency medical costs abroad. |

| Pet Insurance | Manages veterinary costs for illness or accidents. |

| Umbrella Insurance | Provides excess liability protection beyond primary policy limits — useful for higher‑net‑worth individuals or businesses. |

Impact of Insurance Regulations on Coverage

Regulation shapes product design, solvency standards, pricing transparency, and consumer protection. Different jurisdictions have distinct rules — for example, IRDAI governs insurance in India, while U.S. state departments and NAIC model laws influence the U.S. market. Regulators require clear policy wording, fair claims handling, and solvency measures to ensure insurers can meet obligations.

Understanding Compliance in the Insurance Industry

Key regulatory impacts include:

| AspectImpact of Regulations | |

| Licensing | Ensures agents and brokers meet competency and ethical standards. |

| Pricing | Regulates rate‑setting or requires transparent actuarial justification to prevent unfair pricing. |

| Claims Processing | Mandates timely and fair claims handling and recourse processes for consumers. |

| Consumer Protection | Requires standardized disclosures, cooling‑off periods, and grievance redressal mechanisms. |

| Financial Stability | Enforces capital, reserve, and reporting requirements to maintain insurer solvency. |

Principles of Insurance vs General Contract Law

Insurance contracts overlap with general contract law but include special doctrines (e.g., utmost good faith, insurable interest). A concise comparison helps clarify the differences:

| TopicInsurance ContractsGeneral Contract Law | ||

| Duty of disclosure | High duty (utmost good faith) — material facts must be disclosed | Typically caveat emptor or duty to disclose limited; depends on the contract |

| Insurable interest | Required — must have financial interest in subject matter | Not required for most commercial contracts |

| Remedies for breach | Repudiation, avoidance of policy, subrogation available | Damages, specific performance, rescission |

| Formation | Subject to insurance‑specific statutes, proposal forms, and warranties | Standard offer, acceptance, consideration rules apply |

Conclusion

In this article, I looked at the main principles of insurance. These include Utmost Good Faith, Insurable Interest, and Indemnity. They are crucial for understanding insurance contracts.

These principles help manage risks and ensure fairness for everyone. They are vital for good risk management and fair treatment.

Insurance is more than just protecting assets. It’s about planning and making smart choices. Knowing about different types of insurance helps us make better financial decisions.

For example, Life Insurance and General Insurance like Health and Motor Insurance are important. Insurers also play a big role in keeping society stable by managing risks.

Knowing these insurance principles helps us trust the industry more. It also helps us manage risks better. By following these guidelines, we can feel more secure and confident in our financial plans.